[left side]

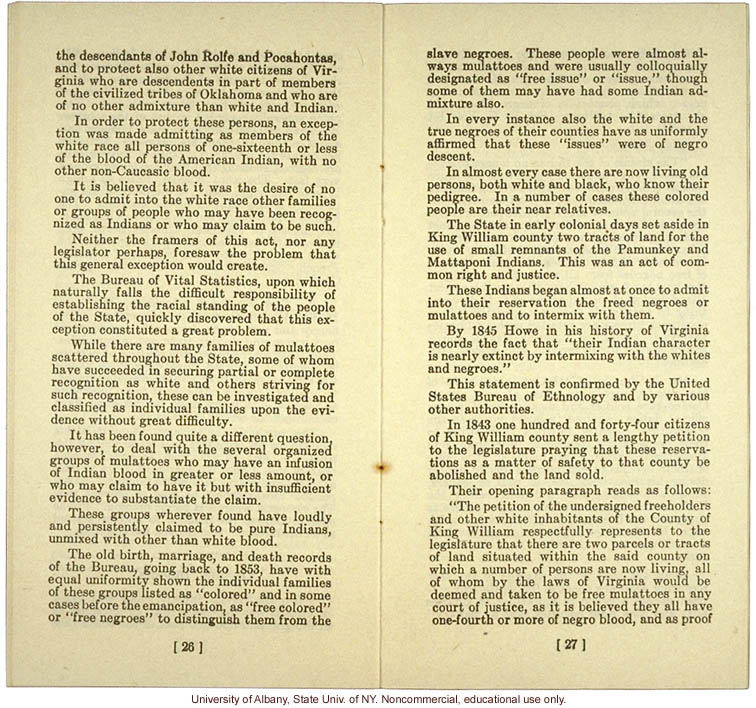

the descendants of John Rolfe and Pocahontas, and to protect also other white citizens of Virginia who are descendants in part of members of the civilized tribes of Oklahoma and who are of no other admixture than white and Indian.

In order to protect these persons, an exception was made admitting as member of the white race all persons of one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian, with no other non-Caucasic blood.

It is believed that it was the desire of no one to admit into the white race other families or groups of people who may have been recognized as Indians or who may claim to be such.

Neither the framers of this act, nor any legislator perhaps, foresaw the problem that this general exception would create.

The Bureau of Vital Statistics, upon which naturally falls the difficult responsibility of establishing the racial standing of the people of the State, quickly discovered that this exception constituted a great problem.

While there are many families of mulattoes scattered throughout the State, some of whom have succeeded in securing partial or complete recognition as white and others striving for such recognition, these can be investigated and classified as individual families upon the evidence without great difficulty.

It has been found quite a different question, however, to deal with the several organized groups of mulattoes who may have an infusion of Indian blood in greater or less amount, or who may claim to have it but with insufficient evidence to substantiate that claim.

These groups wherever found have loudly and persistently claimed to be pure Indians, unmixed with other than white blood.

The old birth, marriage, and death records of the Bureau, going back to 1853, have with equal uniformity shown the individual families of these groups listed as "colored" and in some cases before the emancipation, as "free colored" or "free negroes" to distinguish them from the

[26]

[right side]

slave negroes. These people were almost always mulattoes, and were usually colloquially designated as "free issue" or "issue," though some of them may have had some Indian admixture also.

In every instance also the white and the true negroes of their counties have as uniformly affirmed that these "issues" were of negro descent.

In almost every case there are mow living old persons, both white and black, who know their pedigree. In a number of cases these colored people are their near relatives.

The State in early colonial days set aside in King William county two tracts of land for the use of small remnants of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Indians. This was an act of common right and justice.

These Indians began almost at once to admit into their reservation the freed negroes or mulattoes and to intermix with them.

By 1845 Howe in his history of Virginia records the fact that "their Indian character is nearly extinct by intermixing with the whites and negroes."

This statement is confirmed by the United States Bureau of Ethnology and by various other authorities.

In 1843 one hundred and forty-four citizens of King William county sent a lengthy petition to the legislature praying that these reservations as a matter of safety to that county be abolished and the land sold.

Their opening paragraph reads as follows:

"The petition of the undersigned freeholders and other white inhabitants of the County of King William respectfully represents to the legislature that there are two parcels or tracts of land situated within the said county on which a number of persons are now living, all of whom by the laws of Virginia would be deemed and taken to be free mulattoes in any court of justice, as it is believed they all have one-fourth or more of negro blood, and as proof

[27]

[end]